I’m recording and releasing this a few hours before our parish celebrates the mass of All Souls Day. It’s part of a three-day focus on death and the dead: All Saints Eve on October 31 (or Halloween), the solemnity mass of All Saints Day on November 1, and All Souls Day on November 2. All Saints celebrates those who have died and gone to heaven, where they worship and fellowship in the Presence of the Holy Trinity, and on All Souls, we pray for those who have died in faith, but who have not progressed to heaven. They are, in the words of the Book of Revelation, washing their robes so they may enter the New Jerusalem, doing penance in purgatory.

But today I’m reflecting on something a bit wider: how Catholicism takes death seriously. How it offers a coherent understanding of what death is, and what happens to people when they die. And sound, biblical practices to accompany us through life in anticipation of death, when we die, and for those left behind.

I think Catholicism takes death seriously. Like a grown-up religion should. Which we ought to do, because what’s more inevitable and serious than death?

But we live in a culture that doesn’t take it seriously. There is no coherent understanding of death in America, Canada, and Western Europe. What happens when we die? How should we approach it? What should we do when someone dies? All of this has become individualized. When I was a Protestant Evangelical pastor, it was my responsibility, my privilege, to occasionally be with people as they were dying. Or to plan and officiate at funerals and memorial services. Or to counsel people who had lost a loved one. Or to simply answer questions like, “Where do people go when they die?”

But over the last 40 years, I’d say that it’s become impossible to have really coherent conversations about any of these because there are no consistent beliefs. Americans, Canadians, and Western Europeans each make up their own views on death, the afterlife, how to approach it, how to memorialize it, and what it all means. It seems that every conversation I have with someone consists of listening to them (which is never a bad thing! Always listen!) but listening to them explain or often invent on the fly, what they want to believe.

This person says it means nothing: when your time comes, the lights just go out. Another person says you become an angel in heaven or maybe you become the guardian angel for your loved ones. Someone else says you get absorbed into the universe and become part of the soul of nature. Someone else says now you get to fertilize the trees and reduce carbon load in the atmosphere. Someone says you go to be with your dead relatives. Someone else says you come back and are born as a baby to live another life. Most look puzzled and say they don’t really know, but they’ll just move into “the Light,” whatever that means.

But most think that it will be no big deal. It will all work out OK. Almost no one I meet thinks that they personally will go to hell. They think that really bad people, like Hitler, will go to hell. But not them. If they believe in some sort of God, they’re pretty sure that he/she/or it will agree that they did the best they could and give them a pass.

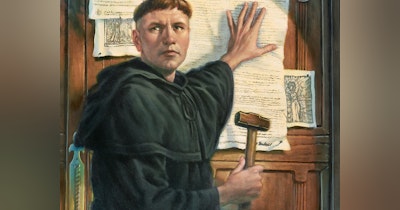

And because beliefs about death are so individualized, there’s no consistency in how we prepare for it. How should we live, knowing that we’re going to die? Catholicism offers this ancient principle: “memento mori,” Latin for “Remember your Death.” Remember that it is coming, and prepare.

And when the end draws near, there’s no consistency for how to meet it. I was recently in a hospice, and they did a great job of making people comfortable and letting them decide what they wanted at the end. You could pet a Golden Retriever, have someone play acoustic guitar, or have a prayer—any prayer, whatever you wanted to hear. Of course, I get that their mission is to serve a diverse population and let the individual decide, but it just reinforced my impression that our culture has nothing to offer you in the end except whatever you want.

And afterward someone passes, we make up our own rituals. You can have your remains sprinkled on a beach, on a mountain, on a roller coaster, put into the garden to make the plants grow, pressed into a synthetic diamond. Whatever.

And we don’t do a funeral anymore, we do memorial services or celebrations of life. Why look at death? We don’t know what to say about it. Better to look back at what we did than forward to where we’re going.

I’m comforted by Catholicism which has, I think, a serious and mature understanding of death. By commemorating the saints we celebrate those who have gone ahead of us. We pray for those souls who are completing their journey in Purgatory. The sacraments accompany us, from baptism at birth, the Eucharist through life, confession, and anointing at the time of death. Our funeral masses pray for the soul to find its rest in Christ. We take heaven and hell seriously.

So today, on the Feast of All Souls, I’m comforted to be a Catholic, to know that my faith, my Church, has solid answers and practical solutions to face the reality that I will, and all of us will die.

--Greg